Making Carbon Markets Work for Faster Climate Action

As it became clear that the COVID-19 pandemic’s destructive force would define the 2020 economy, many wondered whether the decline in market activity would coincide with a dip in global carbon emissions.

But in December 2020, the UNEP Emissions Gap Report clarified that, despite a brief reduction in emissions, our trajectory is still shooting dangerously upward and bound to exceed the constraints on global temperature rise targeted by the Paris Agreement if we fail to change course.

Indeed, the international accord, formally signed in 2016, set out to pursue limiting warming to well below 2°C, while UNEP forecasts a rise in excess of 3°C this century—a scenario that would mean exponentially worse outcomes for nature and people.

There is still time to keep global temperatures within a safer range, scientific reports confirm, but only if the world can find a way to run on half as much carbon as it did in the late 2010s by 2030.

Enabling this low-carbon future requires ambitious commitments and comprehensive approaches right now—including, as UNEP reported, nature-based solutions (NbS). Nature can offer some of the most cost-effective strategies in the climate playbook, provided they’re deployed in concert with a transition to renewable energy, clean transport, and the fiscal reform of fossil fuel subsidies.

So how can countries encourage such a holistic transformation?

If implemented correctly, carbon markets could both accelerate action to combat climate change, and also deliver much-needed co-benefits for nature and people.

Enter carbon markets: perhaps one of the most effective mechanisms available to encourage decarbonization of all kinds. Put simply, these markets put a price on carbon to incentivize businesses to reduce their carbon emissions where it is most financially feasible, and act now to manage the negative effects they can’t eliminate.

One tool used within the market are “offsets,” which allow emitters to balance their excess carbon emissions by purchasing credits from sellers who have a surplus carbon budget—either because they’ve avoided emissions or undertaken some additional activities that reduce or sequester emissions.

Now is our best opportunity

We must take bold steps to address the climate and biodiversity crises by 2030.

Half of all nationally determined contributions (NDCs) subject to the Paris Agreement—representing 31% of global emissions—bank on international cooperation through carbon markets.

But despite their ability to unlock billions of dollars annually for climate action, these markets are not currently scaling up quickly enough. In part, that’s because carbon markets remain a bit misunderstood—but there’s a lot the international community can do to change that ahead of the global climate Conference of the Parties (COP 26) this fall.

Carbon offsets in context: what they’re NOT

It is critical to note that offsetting emissions through carbon credits is not a substitute, but a supplement to the vigorous decarbonization actions that will get us to net-zero emissions as soon as possible.

In other words, they are a near to medium-term solution for difficult-to-achieve reductions on the way to a future where emissions are balanced by carbon sequestration—one we must achieve by 2050 at the very latest.

Realistically, it will take time to drive the technological breakthroughs, improved management, and financial transformation required for delivering longer-term change, and offsets can prevent the emissions gap increasing in the meantime.

In fact, if implemented correctly, carbon markets could both speed up our ability to address climate change, and offer additional benefits to nature and people—especially in the Global South, where much of the potential for credit generation exists.

In the interim, companies must be transparent and ambitious about reducing and reporting their emissions in addition to offsetting a large share of those outputs through the carbon markets, which can enable solutions available today (e.g. renewable energy, NbS) and fund the innovation we still need.

Voluntary and compliance: Making the most of the markets

At present, there are two types of markets that can help accelerate climate action—voluntary and compliance markets.

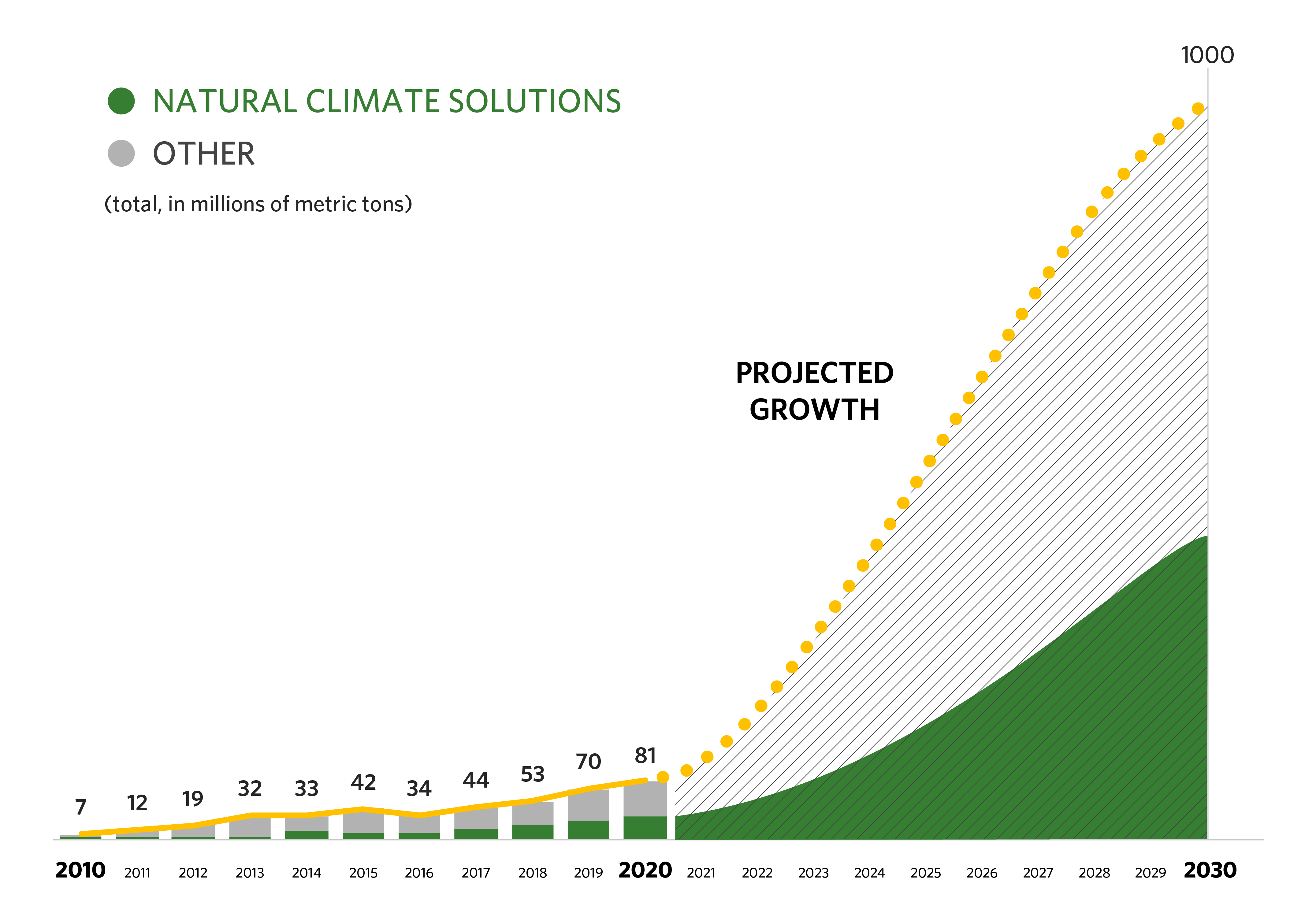

The voluntary carbon market has seen rapid growth in recent years, driven in part by the growing chorus of net-zero commitments made by companies around the world. A recent survey by the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets—an initiative led by the Institute of International Finance (IIF)—estimated that the voluntary market has an opportunity to grow 15-fold in order to fund up to 1 gigaton of additional emissions reductions per year by 2030.

GROWTH FORECAST OF VOLUNTARY CARBON MARKETS TO 2030

The depicted projection assumes NCS market share remains at 2020 levels through 2030. NCS data: WEF, ‘Consultation: Net and Net Zero;’ Overall market growth: IIF, ‘Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets

However, without demand, the market doesn’t exist. And while companies across sectors and geographies are beginning to align their sustainability targets with the Paris goals, they are still insufficient in scale and too new for us to have certainty that this burgeoning market will see a boom.

That said, improving governance to ensure the integrity of these credits and demystifying the transaction process, a key objective of the IIF taskforce, could certainly create favorable conditions for growth.

In addition to the voluntary carbon market, we have the compliance, or regulated, markets. These markets can send clear and predictable signals to participants, because they are established through legal frameworks that can mandate action over a set period of time. In addition, as they are established by governments, they could deliver an even greater level of scale than voluntary corporate commitments.

At the global level there are two such market mechanisms on the horizon. The first is the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), one tool developed to meet the aviation sector’s commitment to carbon-neutral growth post-2020.

While more ambitious goals are needed to bring aviation in line with the Paris Agreement, it is an important first step for the sector and could produce an estimated demand of around 1/3 Gt carbon credits per year by 2030, including from some types of nature-based solutions.

A greater opportunity lies in store later this year when the 190 countries party to the Paris Agreement convene at the COP 26 climate negotiations.

There, provided these parties arrive at a consensus on Article 6, countries around the world could trade carbon credits with one another in order to access more cost-effective emissions reductions, or to sell excess emissions credits if they are going above and beyond their commitments. Reinvesting the annual cost savings from Article 6 trading into further emissions reductions could increase the potential for overall global reduction in greenhouse gases by around 9 Gt a year in 2030, according to a recent study.

This would effectively double the ambition of current country commitments under the Paris Agreement.

The 190 countries party to the Paris Agreement will have the opportunity to create one of the most robust markets ever when they convene at the COP 26 climate negotiations.

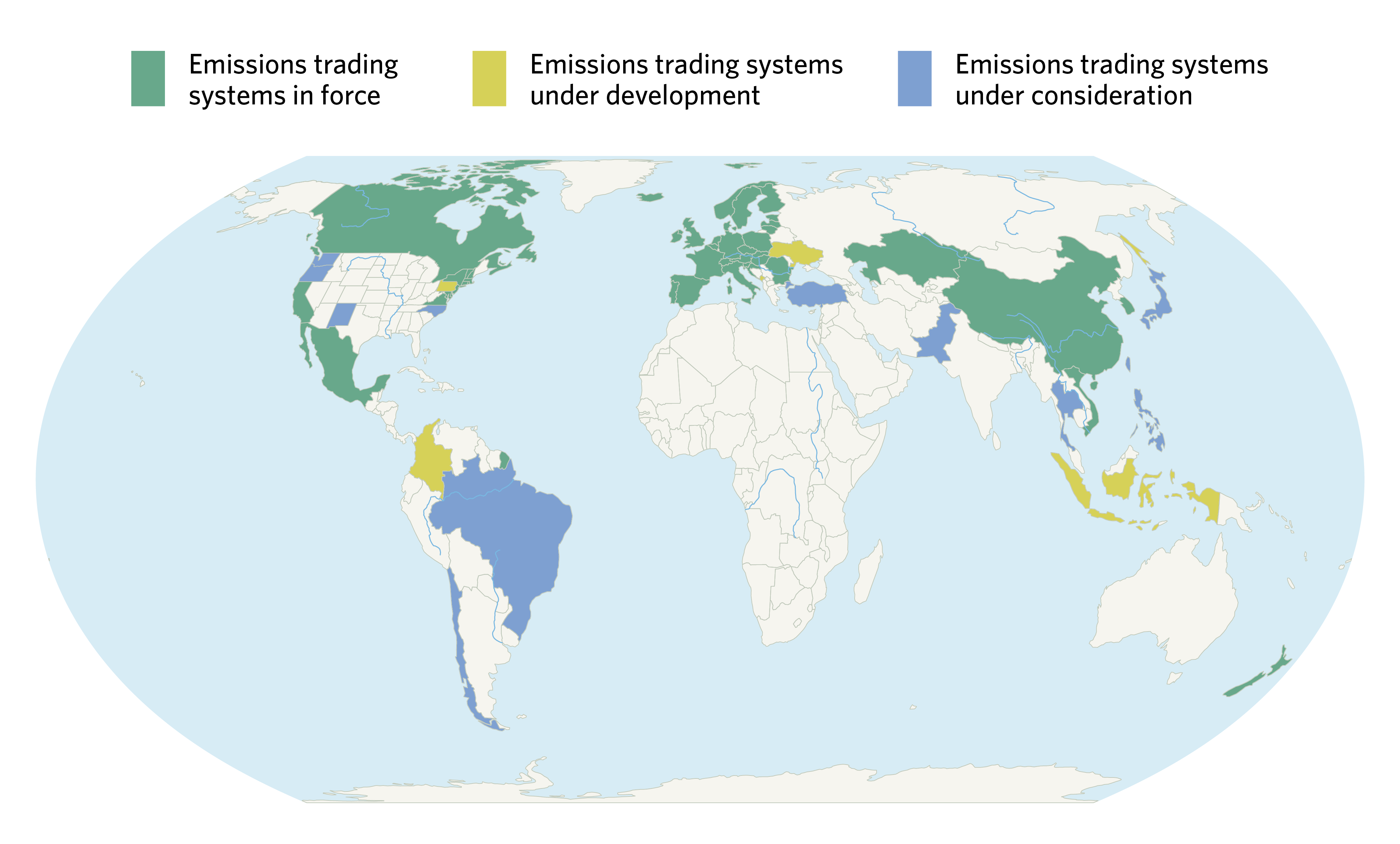

Stepping down from the global level, we have also seen a rise in domestic regulated carbon markets such as those in the EU, South Africa, China, Colombia, and the U.S. state of California.

These domestic markets have the potential to drive scale and increase predictability, which is essential to creating more efficient and effective markets that attract the private sector investment needed to decarbonize our economies in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF COMPLIANCE MARKETS NOW AND IN THE FUTURE

Source: Emissions Trading Worldwide, ‘The state of play of cap-and-trade in 2021,’ International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) Status Report 2021

While the design of all of these markets are continually being improved as regulators and legislators learn and adapt, some of the more mature markets are now showing signs of sending meaningful price signals into the economy—for example the EU emissions trading scheme, currently the world’s largest, has had a market price of over $40 per ton of carbon equivalent (tCO2e) for much of 2021.

As TNC’s Financing Nature report notes, it’s impossible to put a price on the natural world, but we know how much it will cost to save it—and we have the policy and finance learnings to unlock the required funding. Carbon markets are one such strategy in a broad suite of tools that will help us achieve that goal, provided we optimize them at COP 26 and beyond.

We’re already two years into a critical decade for climate and biodiversity action—the action we take now will determine if it’s the decade in which we successfully fund the end of the carbon-based economy.

Courtesy of www.nature.org